The Nile perch (Latus niloticus) is a prominent example of a freshwater fish species that has fundamentally changed the food web of its new habitat and thus biodiversity. | Photo: shutterstock_1545347963

In order to colonize new habitats, alien species must have special adaptive and competitive abilities. Successful non-native species have been predicted to have greater resource use efficiency relative to trophically analogous native species. The research team led by the Brazilian Federal University of Paraná has quantitatively tested this hypothesis in a global meta-analysis of comparative functional response studies. These are studies that compare how many food items are consumed per predator in a given time period at different food densities.

“Not all introduced species cause damage. To assess potential consequences for biodiversity, it is important to identify those non-native species that cause significant negative effects. High predation rates are an important measure here: If non-native species consume many individuals of resident species, this can have far-reaching consequences for species composition and ecosystems,” says IGB researcher Prof. Jonathan Jeschke, one of the authors of the two studies.

70 percent higher consumption rates for invasive species

The maximum consumption rates of alien species in the examined studies were on average 70 percent higher than those of native species. The magnitude of maximum consumption rate effect sizes varied with consumer taxonomic group and functional feeding group, e.g. whether herbivore, carnivore, etc. The researchers found particularly large differences in consumption rate between native and non-native freshwater species. “This could reflect the sensitivity of isolated freshwater food webs to new consumers“, said Dr James Dickey, also an IGB researcher and involved in both studies.

A prominent example is the introduction of the Nile perch (Lates niloticus) into Lake Victoria in the 1960s, which led to the extinction of dozens of endemic cichlid species. According to the authors, competition for resources from invasive species and the associated changes of food webs are likely to increasingly contribute to species extinctions worldwide, especially because habitats and thus food resources are shrinking in many places.

Fight for food in gammarids

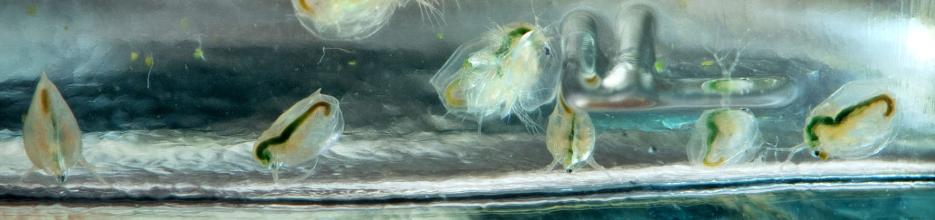

In an experiment, the researchers investigated this fight for food in more detail using two species of gammarids. Gammarids are crustaceans from the amphipod family. They are often dominant and ecologically important species and have been particularly successful in establishing and spreading in their non-native range, especially in Europe. While their impacts are wide-ranging, interference competition with native species has received limited attention to date.

The researchers pitted the North American Gammarus tigrinus against the native European Gammarus duebeni in a battle over a chironomid larva as a single food resource. In the staged dyadic contests, individuals of the native and the invasive amphipod were placed in the experimental arena containing the food resource, and inter- or intraspecific competitor individuals added upon the first individual taking possession of the resource, or after 20 minutes.

The invasive gammarid secures the prey faster and defends it more strongly

Gammarus tigrinus were more likely to take hold of the bloodworm in the opening 20 minutes and did so more quickly than Gammerus duebeni. During this period, they were also less thigmotactic than the native, or “bolder”, being more explorative and spending a smaller proportion of time in the outer zone of the arena. They exhibited more aggressive interactions and activity with increasing size and mass, whereas larger G. duebeni were shown to be less aggressive and less active. G. tigrinus were found to be significantly less likely to lose possession to G. duebeni than they were to conspecifics, whereas G. duebeni were similarly likely to lose possession to G. tigrinus as to conspecifics. “Overall, our results suggest that the behavior and competitive ability of Gammarus tigrinus shown here facilitates its invasion”, said Julian Zeller, who is first author of the study together with James Dickey. He is a Master's student at Freie Universität Berlin.

Findings for the management of invasive species

Preventing the introduction and spread of invasive species is considered the most effective measure to mitigate potential social-ecological impacts. The cost of pre-invasion management is up to 25 times lower than the cost of post-invasion management. “We propose that comparisons of consumption rates and behaviour offer useful methods for assessing the potential impacts of non-native species, and these can in turn facilitate prioritisation and effective prevention of further spread”, said James Dickey.

Also worth reading:

Survey study of local managers on invasive species

The study is the first of its kind to provide an overview of stakeholders' views on dealing with invasive species at local and regional level across Europe. More than 1,900 people from 41 countries took part, with the majority (68%) coming from EU Member States. Respondents consistently reported increasing trends in the number, area and impact of invasive species, despite ongoing management efforts. Local management measures alone cannot adequately address this global and interconnected problem. It is therefore crucial to promote vertical (between local managers and policy makers) and horizontal (between countries) cooperation across Europe.