(a) Global map of light pollution showing large geographical differences ((Illustration: David Lorenz, 2021). (b) The Nile river and its delta in Egypt as a global hotspot of light pollution (photo: NASA Earth Observatory, 2010). (c) Direct light pollution at Huangpu River in Shanghai, China (photo: A. Jechow). (d) Indirect light pollution by skyglow over the River Rhine, Germany (photo: A. Jechow). (aus Hölker et al. 2023)

Light pollution affects all ecosystems

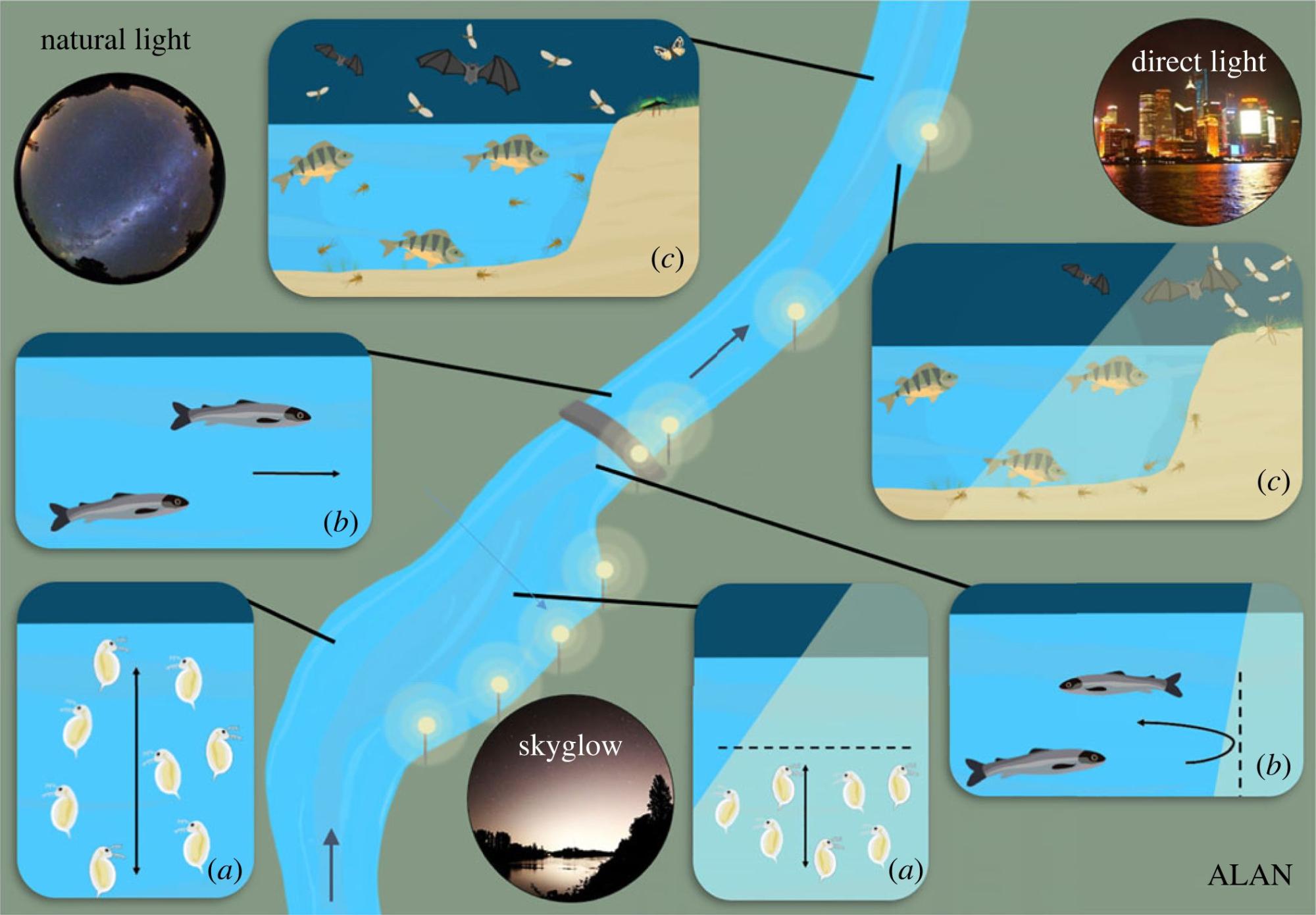

A day comprises 24 hours and provides numerous ecological niches for animals and plants. Around 30 per cent of all vertebrates and over 60 per cent of invertebrates are nocturnal (Hölker et al. 2010). Accordingly, organisms have developed special adaptations to life in the dark over the course of evolution. Light pollution disrupts these adaptations, impairs the sleep-wake cycle of diurnal and nocturnal species, and alters ecological interactions – even underwater (Hölker et al. 2023).

Examples of ecological consequences of artificial light at night (ALAN) along a river–lake continuum, showing interference (a) with zooplankton diel vertical migration, (b) longitudinal migration of fish and (c) predator–prey interactions, including insect drift and effects across the land–water interface. The left side of the river illustrates the situation under naturally dark skies, and the right side highlights the impacts of ALAN. Arrows show the direction of river flow. (Adapted from Hölker et al 2023)

In addition to habitat loss and pesticide use, light pollution also contributes to insect decline. Many insects use the moon and stars for orientation and are irritated and attracted by street lights and other artificial light sources. This so-called vacuum cleaner effect sometimes impacts insects over long distances of up to several hundred metres Manfrin et al. 2025) and leads to exhaustion and an increased risk of predation. Since street lights in Europe are usually spaced 25 to 45 metres apart, illuminated streets often become barriers for light-sensitive insects. Field studies using radar measurements also show that only about 4 per cent of flying insects affected by light actually reached the street lights. This means that moths not only lose their orientation directly under street lamps, but their flight behaviour is already disturbed outside the light cones. Therefore, the negative impacts of light pollution are probably greatly underestimated (Degen et al. 2024). Even very low light intensities below the full moon level (< 0.3 lux) can trigger physiological changes in animals and plants by suppressing melatonin (Grubisic et al. 2019).

Minimum levels reported in the literature to suppress melatonin production in different vertebrate groups relative to light levels by natural and artificial light sources (using human-centric metric lux). Illuminance during day, twilight, and night as a function of elevation angle of sun and moon; yellow solid line: sun illuminance on clear day; light yellow dashed line: moonlight of full moon. The second value for humans marked with an asterisk in the light blue column extended downward indicates the threshold for monochromatic blue light above which melatonin synthesis was suppressed under controlled laboratory conditions. Source: modified after Grubisic et al. (2019), icons made with Freepik (https://www.flaticon.com).

Legal protection against light pollution

Scientists agree: artificial light at night is a significant stressor for flora and fauna. It impairs orientation, movement, reproduction and population dynamics and has far-reaching ecological consequences. Nevertheless, legal protection of flora, fauna and habitats from light emissions has been insufficient to date (Schroer et al. 2020). With the amendment of the Federal Nature Conservation Act in 2021, Germany has for the first time enshrined protection from light emissions in § 41a BNatSchG n.F. as part of the National Action Plan for Insect Protection (Huggins 2023, Huggins und Zimmermann 2022). However, the provision will only come into force with the enactment of a corresponding ordinance based on § 54 Abs. 4d, 6b BNatSchG, which the Federal Government has announced as part of the National Biodiversity Strategy by 2027. With this background, the Federal Government has entrusted the IGB Working Group on Light Pollution and Ecophysiology with a research and development project (FKZ: 3523 82 0600) to develop regulatory approaches on how outdoor lighting can be regulated in a scientifically sound and legally rigorous manner to protect animals and plants.

What can we do?

By specifically controlling light direction, illuminance, lighting times and, where necessary, light colour, it is possible to achieve lighting that follows the principle of ‘as much as necessary, as little as possible’. Luminaires can be technically installed and aligned in such a way that only the space were we humans need light is illuminated. This is because light intensity and light colour have different effects depending on the organism (Czarnecka et al. 2025). It is particularly helpful to avoid light emissions altogether – either by switching off lights when they are not needed or not installing them in the first place, or by shielding them consistently so that they are hardly noticeable to organisms outside the area to be illuminated.

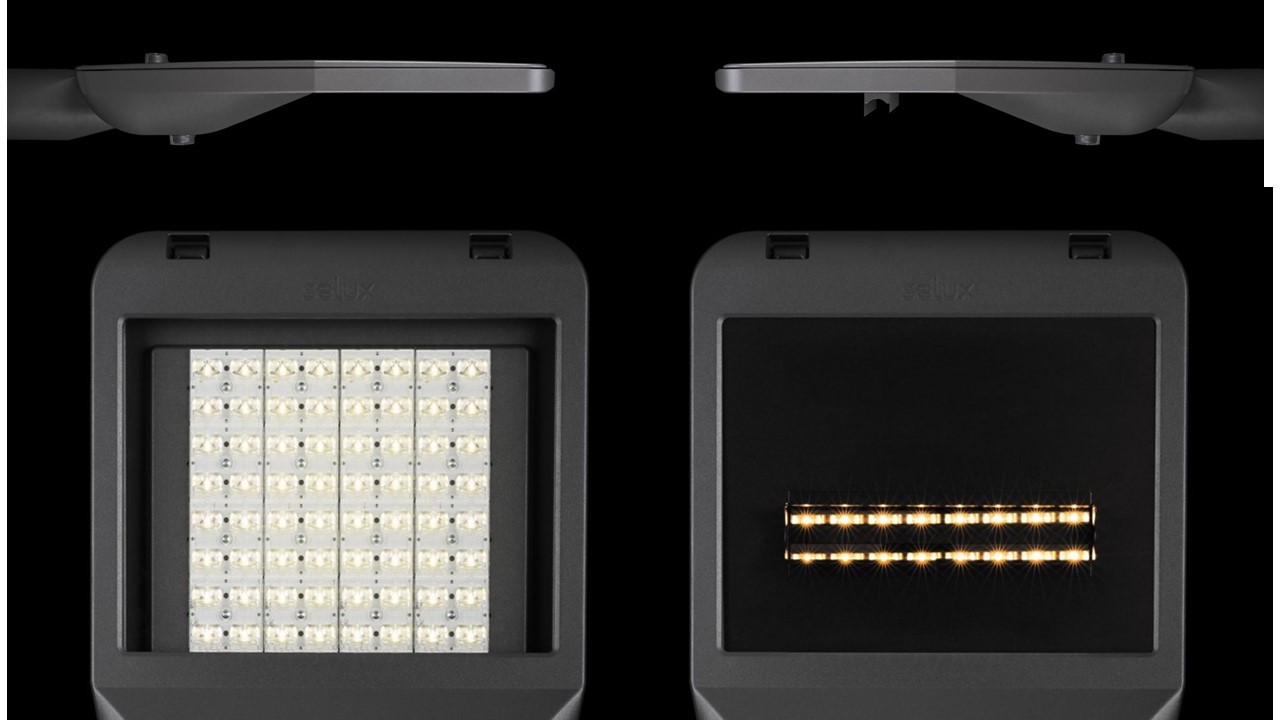

Lighting before (left) and after der Conversion to shielded luminaires with optimal light control (Tal Shield), copyright: Andreas Jechow.

In the project Species Protection through Environmentally Friendly Lighting (AuBe), a luminaire was developed in collaboration with Selux GmbH and the Technical University of Berlin that specifically shields and directs the light at the luminaire head. This means that only the actual width of the path is illuminated, without brightening adjacent green areas. Studies show that these luminaires attract significantly fewer insects of all orders and that insect communities in areas illuminated like this are similar to those found in unlit areas – including light-shy species (Dietenberger et al. 2024). However, these effects have so far only been observed in flying insects. The impact on ground-dwelling species and entire ecosystems has not yet been sufficiently researched (but see van Koppenhagen et al. 2025). Where light is not required, there should therefore be a right to natural darkness.

Changes to the TAL luminaire from Selux GmbH. Left: Conventional TAL luminaire, top: side view, bottom: underside of the luminaire head. Right: TAL Shield with shutters (top, side view) to shield light emission and with passe-partouts to reduce the light emission area (bottom). These measures enable targeted illumination of the path width and prevent light radiation into adjacent areas.

Awarded the German Sustainability Prize

The ‘Tal Shield’ luminaire, developed by Selux GmbH in collaboration with TU Berlin and the IGB, received the German Sustainability Prize in 2025 as an outstanding transformation product in the category Nature. The jury praised the scientifically based development of the Tal Shield as a solution that creates a balanced interplay between human needs and ecological requirements. More information on the development of the luminaire is available on the Selux GmbH website.

Transdisciplinary communication

Effective solutions require the consideration and integration of many different perspectives and areas of expertise. The IGB therefore is eager to overcome interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary barriers between science and politics. Lighting designer Catherine Peréz Vega analysed the particular challenges and potentials associated with these barriers using light pollution as an example. Her dissertation was awarded by the German Lighting Society in 2025.

Links and downloads

- BfN-Skript 543: Schroer, S., Huggins, B., Böttcher, M., & Hölker, F. (2019). Leitfaden zur Neugestaltung und Umrüstung von Außenbeleuchtungsanlagen: Anforderungen an eine nachhaltige Außenbeleuchtung. Deutschland/Bundesamt für Naturschutz.

- EUROBATS - Leitfaden für die Berücksichtigung von Fledermäusen bei Beleuchtungsprojekten: Voigt, C.C, C. Azam, J. Dekker, J. Ferguson, M. Fritze, S. Gazaryan, F. Hölker, G. Jones, N. Leader, D. Lewanzik, H.J.G.A. Limpens, F. Mathews, J. Rydell, H. Schofield, K. Spoelstra, M. Zagmajster (2018): Guidelines for consideration of bats in lighting projects. EUROBATS Publication Series No. 8. UNEP/EUROBATS Secretariat, Bonn, Germany, 62 pp, Guidelines for consideration of bats in lighting projects (PDF).

- Stellungsnahme COST Action ES1204 “Loss of the Night Network” (LoNNe)

- Dokumentarfilm Verlust der Nacht (20 Minuten)