Local pottery in Sicily with prickly pear cactus cladodes. | Photo: Ross Shackleton

The study reveals how some invasive species may be embraced by local populations as familiar and cherished elements of their local environment, often complicating efforts to manage them. “This represents a phenomenon of ‘cultural integration’ – a process where invasive species become embedded in local traditions, identities, and everyday life”, said Ivan Jarić, researcher from the University of Paris-Saclay in France and the Czech Academy of Sciences, and lead author of the study.

Examples of cultural integration

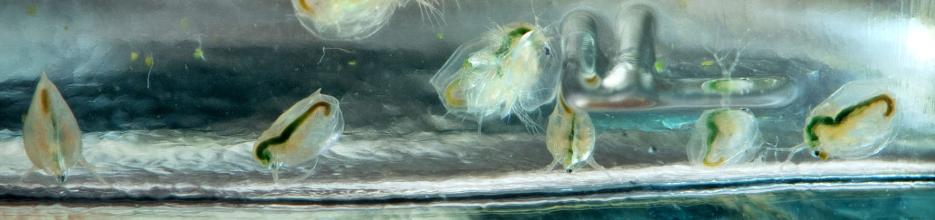

Whether it is a plant used in traditional recipes or an animal celebrated in local festivals, the cultural acceptance of these species is reshaping the way people relate to nature. For example, the prickly pear cactus, originally from the Americas, is now a familiar sight across parts of Africa, Asia, and Europe. In rural areas, some people rely on it for their livelihoods – gathering and selling its fruit, which shows up in local dishes and recipes, and using it as a fodder plant during dry months. But over time, it has become more than just a useful plant. In some places, people have forgotten it ever came from somewhere else. It is woven into folk tales, art and crafts – and even taken on the role of a local symbol in some areas.

Or an example of a wetland plant: Once cattail (Typha domingensis) became commodified as a popular resource for handicrafts, local communities in Mexico started to intentionally facilitate its invasion, which is negatively affecting the native California bulrush (Schoenoplectus californicus), a culturally valuable and important wetland plant.

Consider the cultural aspect when managing invasive species

While cultural integration can bring some benefits – including new sources of food, recreation, or ecological services – it also comes with significant challenges. Once an invasive species is culturally accepted, it becomes much harder for conservationists to control or remove it. Public resistance can stall or even block crucial management interventions. However, eradicating such culturally integrated invasive species is not always the best answer. In some cases, removing them can trigger unexpected damage to ecosystems – and disrupt local cultures, livelihoods, and economies where these species have become embedded.

To manage invasive species wisely, we need more than just biological science. A fuller, more inclusive approach must also draw from social sciences and the humanities. “Conservation efforts should not only be scientifically sound but also socially and culturally aware”, suggested Jonathan Jeschke from the Leibniz Institute of Freshwater Ecology and Inland Fisheries (IGB) and Freie Universität Berlin, last author of the study. Ivan Jarić added: “Decisions should be based on solid science and include the voices of local communities, stakeholders, and rights holders. Bringing everyone to the table early – especially those with first-hand knowledge – helps build trust, reduce conflict, and create solutions that balance ecological, cultural, and economic needs.”

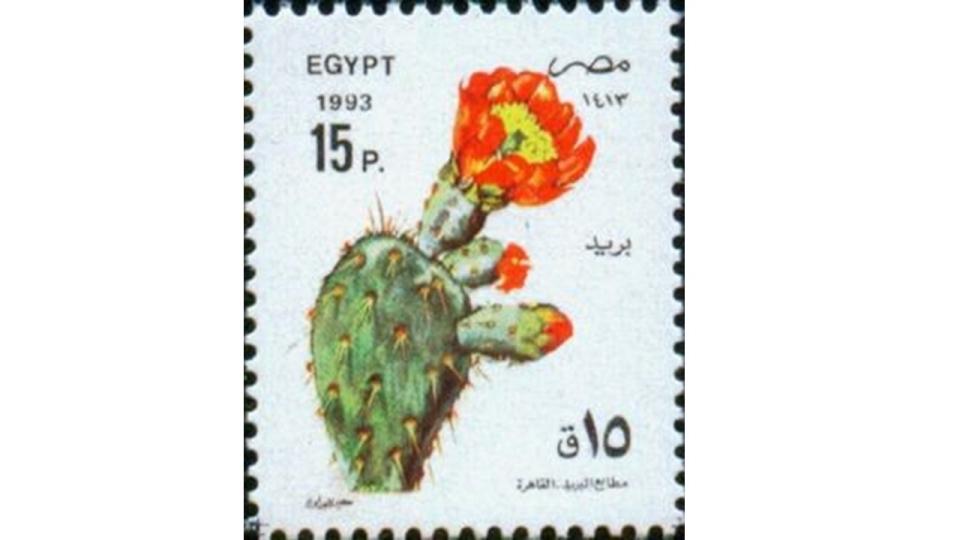

A stamp with prickly pear cactus from Egypt. | Photo: Ross Shackleton

Locations of numerous bars, restaurants and hotels named after prickly pear cactus in Sicily. | Photo: Ross Shackleton

Prickly pear cactus on a popular touristic beach in Sicily. | Photo: Ross Shackleton