The water level is subject to natural and human-made fluctuations. | Photo: David Ausserhofer

Rivers usually only come into focus when ships can no longer navigate them or when regions are flooded. It seems as if our watercourses either have too little or too much water. Let's start with "too little".

Many watercourses are heavily regulated and do not have a natural water level

Photo: Maria Warter

The fact that rivers in this country are carrying less and less water is often not clearly visible. This is because many rivers are flow-regulated. This involves reinforcing the banks, dredging the riverbed to create a navigation channel, and installing locks and weirs to regulate the inflow and outflow. “As a result, a constant water level is perceived as normal,” said geoecologist Dr Tobias Goldhammer. One example of this is the section of the Spree in Berlin. Its water level is heavily regulated by locks. “Without this adjustment, the Spree would carry less than half as much water locally in summer“, said the researcher.

The Spree's already low water level will decrease further in future due to the end of opencast mining in Lusatia. This is because mining has artificially increased the Spree's water flow for over a century by pumping and diverting groundwater into it. Climate change exacerbates the threat of water scarcity in the Spree. This is a development that affects many watercourses worldwide.

More and more rivers are temporarily drying up

Photo: Hauke Dämpfling

In fact, many rivers dry up temporarily; worldwide, this applies to more than half of all watercourses. The organisms living in these rivers have adapted to natural fluctuations and seasonal rhythms. “A changing water level can be an important environmental stimulus for behaviour and life cycles, such as migration or reproduction. However, the increasing trend is worrying", said Professor Sonja Jähnig.

The frequency, duration and extent of drying up have already increased dramatically as a result of climate change, extensive river straightening, the loss of retention areas such as floodplains, and rising human demand for water. In arid and semi-arid regions — areas with a maximum of three to five wet months per year — intermittent watercourses are the predominant type of surface water.

As rivers dry up more and more, longitudinal connectivity becomes ingreasingly important

When larger watercourses carry less water or individual sections dry up, aquatic and semi-aquatic animals have less habitat available. “Drying river sections can also become ecological traps. This makes physical longitudinal connectivity all the more important, i.e. ensuring that the river is not permanently interrupted by human structures such as weirs and dams“, said ecologist Dr Franz Hölker.

His research group studied the behaviour of Italian southern minnows (Telestes muticellus), an endemic carp-like species in northern Italy, in an intermittent mountain river before, during and after two severe droughts. A high proportion of the fish survived the drying riverbed by migrating upstream. In relatively natural systems, fauna can thus seek refuge to survive dry periods. Interestingly, the fish increased their range during flood events, suggesting that these play an important role in downstream and upstream dispersal in small mountain streams.

New situation: Lowland streams in temperate latitudes also increasingly affected

Lowland watercourses in temperate latitudes are now also increasingly affected by drought. In large, multi-year field experiments, Professor Dörthe Tetzlaff is investigating the water balance of the landscape at one such lowland watercourse, the Demnitzer Mühlenfließ in Brandenburg. The long-term data collected by the IGB in this region over the last 30 years is helping in this research. "If you compare today's data with that from the 1990s, this groundwater-fed watercourse is drying up for longer periods and with increasing frequency. In 2019 and 2022, the period without runoff in the Demnitzer Mühlenfließ exceeded 150 days per year. Similar trends are emerging in an increasing number of watercourses in Brandenburg", explained the ecohydrologist.

The reasons for this are lower soil moisture and falling groundwater levels. In smaller, groundwater-fed watercourses, the normal seasonal cycle has three typical periods: in winter, the watercourse is continuous and the groundwater and soil reservoirs are replenished. In spring, they begin to dry up in places as a lot of water is absorbed and evaporated, particularly by vegetation during its active growth phase. Heavy rain in summer increases soil moisture in the upper layers in the short term, but does not raise the groundwater level, meaning surface water is hardly fed by it. During such events, a lot of water quickly flows off the surface via artificial drainage systems. It is only during prolonged rainfall in autumn and winter that such watercourses are fed continuously again by rising groundwater. However, many of these watercourses now also dry up during the winter months. For example, the Demnitzer Mühlenfließ had no water at all until the end of January 2023 in the drought year of 2022.

Having less water also leads to poorer water quality

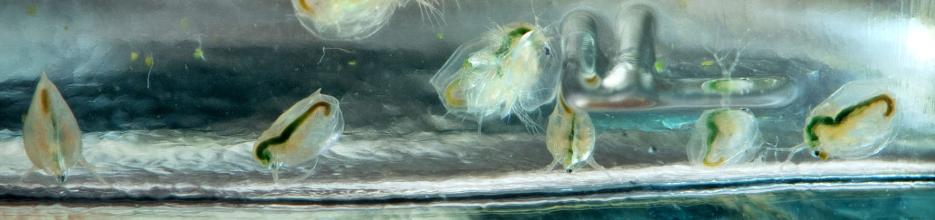

Photo: Angelina Tittmann

Such shortages often result in poorer quality. Research by Dörthe Tetzlaff shows that intermittent lowland rivers in Central Europe are becoming increasingly polluted with nutrients and depleted of oxygen. "Climate change is altering the role of rivers: instead of transporting substances and biomass, they are becoming stagnant reactors in which completely different metabolic processes take place“, explained the researcher. In addition, more greenhouse gases are released from the drying areas of the surrounding landscape and during the rewetting process.

Tobias Goldhammer and his colleagues have also observed that nutrients and pollutants accumulate when there is less runoff in the Spree and other watercourses in Berlin, such as the Panke and Erpe. "There is an additional challenge here: due to lower precipitation, the water in flowing watercourses consists to a large extent of treated wastewater, around 80 percent in dry summers", said Tobias Goldhammer.

Low water levels also lead to the accumulation of nutrients and pollutants in lakes

As with rivers, the water level in standing bodies of water fluctuates naturally. “At Lake Starnberg in Bavaria, for example, the water level is not regulated, so it can vary by about half a metre depending on the season”, said Professor Michael Hupfer. He is investigating how lakes are changing in the long term as a result of climate change. “However, many lakes, especially in north-eastern Germany, are affected by unusually low water levels. Examples include Lake Arend in Saxony-Anhalt and Lake Seddin in Brandenburg.“

Michael Hupfer participated in a nationwide preliminary study of 52 lakes which showed that 71 percent of these lakes experienced a decline in water levels between 1985 and 2022. Depending on the size of a lake, falling water levels can increase its warming and change its stratification behaviour, adversely affecting the oxygen and nutrient balance. Increasing evaporation and longer water retention times also lead to the concentration of nutrients and pollutants in standing water. Together with higher temperatures, this results in more severe algal blooms.

Floodplains, moors and land use mosaics: nature-based solutions can help retain more water in the landscape

Photo: David Ausserhofer

How can increasing drought be counteracted? “In fact, the type of land use can have a significant impact on the water balance“, said Dörthe Tetzlaff. In cooperation with farmer Benedikt Bösel, her research team was able to show, among other things, that under ‘mosaic-like’ land use such as agroforestry, less water is lost through evapotranspiration in the landscape than in pure coniferous forests, while at the same time increasing infiltration rates, which is important for groundwater recharge. The reintroduction of beavers has also led to more water being retained in the landscape and thus more being fed into the groundwater. “These are nature-based solutions that we should increasingly rely on in dry Brandenburg“, said Dörthe Tetzlaff.

Connecting with floodplains stabilises the water balance and creates habitats

Another nature-based solution is to reconnect watercourses with their floodplains in order to create refuges for living creatures, form water reservoirs and stabilise the water balance.“When a river is straightened and canalised, the water also flows out of the landscape more quickly. Floodplains are important retention areas for water and nutrients. They help to retain water in the landscape and purify it“, said Dörthe Tetzlaff. She demonstrated this, for example, using the polders on the Oder, which are open all year round, as part of joint research work with the Lower Oder Valley National Park.

When there is ‘too much water’: floodplains mitigate flood waves downstream

Photo: David Ausserhofer

Floodplains are also an important natural flood protection measure. "We talk about a river bursting its banks, but there is actually no fixed bank line for a natural watercourse. This example from everyday language shows that we need to change the way we think. We should not see flooding as a danger, but as a natural part of the river system that regularly connects bodies of water and the surrounding landscape. This enables the exchange of water, substances, fauna, and materials", said Sonja Jähnig. The scientist is primarily concerned with restoring conditions to a more natural state, for example by relocating dykes and adapting human use.

In a study, she investigated the effectiveness of various nature-based solutions for flood protection. One successful example is the Lenzener Elbtalaue project. The project's key measures on the Middle Elbe were the construction of a new seven-kilometre-long dyke further inland and the selective removal of the old dyke. This gave the river an additional 4.2 square kilometres of floodplain. Consequently, the flood peak of the 2013 flood was reduced locally by almost 50 centimetres.

The biodiversity strategy target has been missed: instead of increasing floodplain areas by ten per cent by 2020, only one per cent has been achieved

To accelerate the return of endangered species, new flood basins were created in the Elbe floodplain. These basins are fed by floodwaters and provide diverse habitats for fish, amphibians, and birds. Floodplains are hotspots of biodiversity. This is why the National Biodiversity Strategy stipulates that floodplain areas in Germany should increase by ten per cent by 2020; however, to date, only one per cent has been achieved. “Our overview study has shown that there are solutions for stabilising the water balance of watercourses that offer multiple benefits to humans and nature”, said Sonja Jähnig.

Legal frameworks already exist to better protect our waters against drying out and to implement more natural measures against flooding. The European Green Deal, for example, enables cross-border flood management; the EU Biodiversity Action Plan promotes the ecological management of river basins; and the EU Biodiversity Strategy aims to protect 30 per cent of the land area. Researchers conclude that these opportunities must be exploited more effectively.